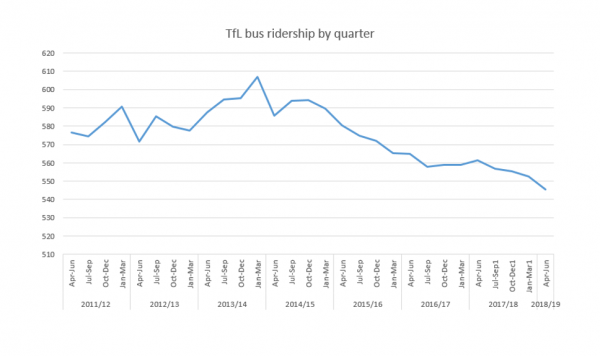

Bus use in London has now fallen c 8-10% from its quarterly peak in Q1 January-March 2014 to the latest data covering the period until June 2018.

For more than 20 years the simplistic narrative has run as follows: "London buses are regulated. London ridership is growing. Therefore, London growth is due to regulation".

This was never the whole truth. Buses in London have benefited from unique levels of traffic restraint, population growth and subsidy. London has become ever denser, and ever more unwelcoming to cars. Urban employment in the metropolis is booming, and increasingly concentrated - creating ideal conditions for bus demand, if not for bus costs.

Few of these conditions apply in the city regions which are taking on new powers over buses. Regional population levels are generally flat, city centre activity is moderate-to-weak and urban rail improvements have bitten deeply into bus demand on key corridors in a way that does not apply in London.

However, London has now passed a tipping point. Starting in 2017 it became clear that changes to both market conditions and TfL's own policy priorities have changed the capital's bus equation fundamentally.

Since 2016 cycling has been prioritised in central London to a unique level, removing significant bus capacity along key routes and at key junctions. At the same time, other factors have acted to increase traffic congestion, including the growth of delivery vans and the expansion of Uber-style private hire vehicles.

The much-vaunted congestion charge has long since faded - diminished as an effective policy tool by TfL's very high cost of collection, the resultant low net yield and a general political unwillingness to set the charge at the 'clearing' level that will reduce congestion in 2018 conditions. In any case, the issue in central London appears to be loss of highway capacity, and not an excess of motor vehicles.

Buses are also impacted by the on-going behavioural change arising from the growth of on-line retailing and easy home working. The data is unclear, but it may be that long-established trip rates are weakening, and we are seeing the long-feared reduction in commuter and shopper trips.

Far from growing, London bus use is now falling sharply, with the largest reductions seemingly correlated to TfL's own highway changes.

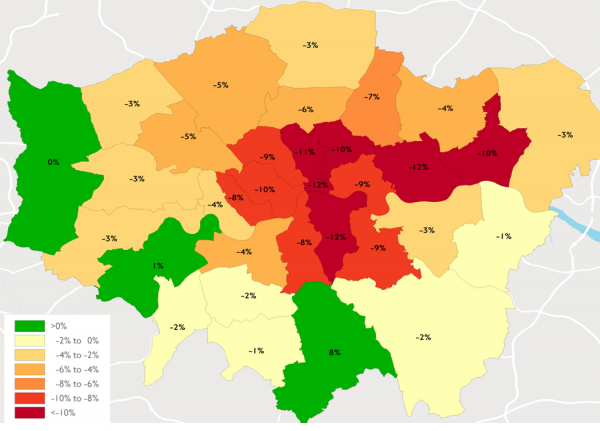

TfL's consultation document describing the proposed bus cuts includes a fascinating map that details the falls in bus demand by borough. This highlights the stark drops in central London and the inner suburbs, with falls of up to 12% between 2015 and 2018.

TfL diplomatically link this to the cycle policy - Our investment in walking and cycling infrastructure, as well as improvements to the Overground and Tube network, is starting to change how our customers use the bus network. That's one way of putting it: less politely, buses in central and inner London are now so slow that they struggle to compete with walking for shorter trips, let alone cycling or rail.

London buses now face a toxic economic environment of rising costs, driven by London's competitive labour markets and falling bus speeds, leading to weakening revenues. TfL is therefore planning substantial cuts to bus mileage – with many routes being shortened, and or reduced in frequency and some being deleted altogether. Many of the cuts will occur once Crossrail has opened, releasing further central area tube capacity, but TfL has already gone to consultation, and the scale of the reductions is starkly visible, and extends well beyond the east-west Elizabeth Line axis.

One can only imagine the reaction to this kind of contraction in one of the regional cities.

TfL has consciously chosen to prioritise cycling over buses as the priority user of road space. It seems not to have fully considered the impact such a policy would have on bus use. Bus speeds in central and inner London are now extremely low – in many places at walking speed. The overall cost-benefit case for London's cycling policy remains unclear, but the London experience further highlights the fundamental issue of journey speed in mode choice.

What does this mean for the city mayors and provincial bus companies ?

Road space remains a scarce commodity: hard choices will need to be made about who gets to use limited space. London has proven that there are trade-offs. It is not clear that cycling is the best use of such scarce road space – especially given that the TfL cycle hire system requires bikes to be moved between docking stations by carbon emitting lorries. Similar schemes in the regions, could have even more drastic effects.

Secondly, the falls in bus demand in London are despite a generally favourable economic climate. London bus use should be growing. Reversing bus decline in the regional cities will be much harder.

Thirdly, TfL will need to define a clear role for the bus. The London bus is ceasing to be the all-purpose Omnibus we once knew, and will increasingly occupy a niche role between cycling, rail and ride share, serving those who are unwilling or unable to walk and cycle or cannot access rail services. This is an inevitable consequence of the extremely low commercial speed that buses in London can achieve.

David Leeder is Managing Partner of strategy consultant Transport Investment Limited